Anyone can become a great chef—if you have the right emotional training to back you up!

Benjamin Zander, famous orchestra conductor and co-author of the ‘Art of Possibility’ has a story to tell.

Benjamin had a twenty-five year old problem.

He had thirty students that were going to go through two semesters of training with him. The students were all instrumentalists and singers. They were going to learn the art of musical performance, including the psychological and emotional factors that stand in the way of great music-making. Yet, in twenty-five years, he wasn’t able to get the class to do what he wanted them to do. Namely, to take risks with their playing. They’d always be so anxious to succeed, that they’d stay on the straight and narrow.

And then Ben (and his wife Roz) came up with an emotional super-charger

They decided to give every single student an A. No matter what they did during the year, the student would get an A.

Of course, this seemed unfair. Should the slacker get an A, even though another student has put in ten times the effort?

Technically this seems weird, but look at the emotional ramifications.

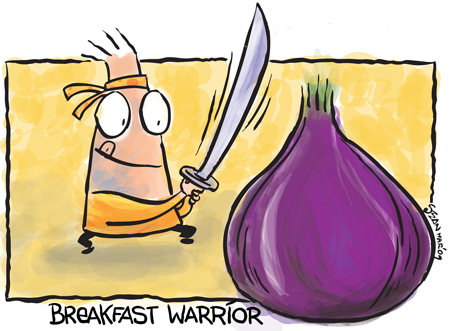

Imagine if you could learn to draw cartoons, and there was no such thing as a bad cartoon.

Imagine if you could write an article, and there was no such thing as a bad article.

Imagine you could paint a picture and got an A.

You can’t imagine it, can you?

But ask a cartoonist, or a reporter, or a painter to do the corresponding tasks above, and they’ll do it without too much of a frown.

And if you look back into their history, you’ll find something consistent.

You weren’t told that you were a great cartoonist. Your drawings weren’t put up on the fridge. Your parents didn’t get you a whole bunch of drawing books, and let you paint on the walls. You were instead told, that art was for the other talented people. That no one in your family was an artist. That it’s ok if you can’t draw. And that’s not what happened in the house of the ‘cartoonist.’

In that house, the cartoonist knew one thing. That he or she would get an A if she drew something.

That the mother and father, and teacher, and grandparents—even the dog would be all excited when you did your cartoon.

That when you went to school, your friends would egg you on to draw cartoons.

That your cartoons happened to be a chick/guy magnet and got you prominence.

All the while the brain is going: Hey this is good.

Emotions of success fill your brain.

Failure pops in, says hi, but the success is so overriding, because suddenly you’re seeing yourself as an A student already.

And hey, now you’re talented.

But how do we know this to be true?

Words and actions have enormous emotional ramifications.

If someone tells you you’re really good at ‘cartooning’ for instance, a couple of things happen.

1) You begin to like that person more.

2) You begin to see your own work in a new light

Liking that person more, means you get pre-disposed to impressing that person. So if the person says: “You really dress well” then you’re more than likely to dress well each and every time you go to see that person (even if you’re quite casual otherwise). And then, in the process of dressing well, you feel better. And you see your own dressing in a new light. You can now spot smart casual from casual. You are now suddenly progressing along the line—if only to impress one person.

Of course, this leads to other people noticing your new ‘talent.’

This starts a bit of a Domino Effect. You think, there you are. And therefore you become what others believe you are.

And this magnificent journey begins with a simple comment, or series of comments.

Comments that make you feel good. Comments that make you smile. Comments that end up with your ‘talent’ becoming a chick magnet.

The A starts in a single moment.

Which brings us right back to Benjamin Zander and his students.

He got each student to see themselves at the end of two-terms. And to write a letter to him saying: “Dear Mr. Zander…I got my A because of…”And in this letter they had to give as much detail as they could; the story of what would have happened during the year; and what would have happened to the student as a result of this A grade. And everything needed to be written in the past tense.

Would you live up to your A?

Would you live up to be a ’smart dresser?

Would you live up to being a superb cartoonist?

You see, it’s all emotion. Because Zander’s students haven’t achieved anything. But do you have any doubt about the outcome? That’s the power of emotion. That’s the power of your brain. And that’s why talent is a myth.

Next Up: Find out—Why Nightingales Sing In Tune: Decoding the Mystery of Talent

great story Sean. Had heard about this before but your onion twist makes it even more eye tingling

i also feel like answering to susan greene – who feels like talent in sort of NATURE and in built and not NURTURE….there is huge debate about all this – and it is STILL – “the jury is out”. There are many who pick up “talent” like singing, piano, sports, art etc at a very late stage in life ( no pressure) and turn things around and perform miracles even –

I disagree. Talent is not a myth. You can learn a skill, but talent is what you’re born with.

An example. Two people take ballet lessons. One has natural talent, and the other does not. They both learn the exact same dance and can perform the steps flawlessly. Yet any person watching the two of them dance could immediately tell which person has talent and which one does not. The one with talent will have a grace and fluidity that the non-dancer will lack. That isn’t to say the non-dancer can’t improve, or shouldn’t continue working on her skills, but she’ll never be talented, because talent can’t be learned.

There’s no real proof that talent is what you’re born with. In fact it’s just something we’ve been told as we’re growing up. Anyone can indeed learn a “talent” and become exceedingly good at it with good pattern recognition, a good teacher and a good methodology.

Physical ability is different though. Some people have a built that makes them stronger or taller. But as far as talent goes, it’s often sheer hard work combined with pattern recognition.

If talent were inborn, then we would need to do nothing to develop it further. It would allow us to be born geniuses and stay geniuses for life.

This is so true. I’ve had this discussion loads of times. How does someone become and artists, photographer, writer etc. They decide that they are, it’s that simple. Then one by one people agree suddenly you have an audience who appreciate you, others here and the ball rolls forward.

Great post, inspired me this difficult Friday morning.

In fact, for instance, you could take a person (even unwilling at the start) and make them outstanding in a skill such as copywriting or cartooning, or something that is considered to be quite um, ‘creative’. And you can do that in six months or less.

And this doesn’t even require them to be willing to learn the skill. Of course there will be some ‘persuasion’ involved, but here’s how it works.

Let’s say you were in a strange country, on a strange island and the only way you could ever communicate was to draw cartoons. Believe me in six months you’d learn to draw cartoons.

As I travelled through Europe, I met people who worked menial jobs who taught themselves German, French, Polish and Spanish (sometimes all four) simply because there was no choice but to do so. These weren’t some highly intelligent folks. These were folks who were illegal immigrants, and who had to learn the languages even while moving through countries.

Are they PhDs in language? I doubt it. But their mastery in a few months of a brand new language is akin to talent. Talent is just another word for language. If you can learn a language, be it Photoshop, or programming or anything else, you can learn to be talented.

After that it’s down to sheer practice, a good teacher and pattern recognition. I’m sure we have doubts about it, but those doubts were implanted in our heads by teachers, parents and friends who never told any of us that we could be anything we like.

That talent is indeed just a language. 🙂

Actually what we say as talent is a small difference magnified by practice over time. Whether its legendary singers doing riyaaz every morning or golfing champs like Tiger Woods or Vijay Singh slogging it out on driving range to perfect every inch, talent and spectacular peformance with ease invariably has tremendous pratice behind it. A more eloquent and studied treatise on this idea is the book Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell. Highly recommended for anyone with strong views or questions about talent vs effort vs lucky break.

And here’s just a little um, research.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/07/magazine/07wwln_freak.html?_r=1

I agree with you Sean, 100%. I used to think that the ability to draw well is a talent. My wife taught me to draw in about 6 lessons. While I didn’t practice enough to get really good, I clearly knew that, “I can’t draw a straight line” is a myth. The fact that she has viewed herself as an artist since she was 5 years old and has put in thousands of hours into practice is why she is so good at what she does.

Everything is a learned skill. I doubt anyone would say that it takes talent for a person to read and write. Yet it is the same process. Every learned person 200 years ago had beautiful calligraphic handwriting, something that would clearly be viewed as talent in today’s culture.

To speak to Susan’s initial comment at the top about the girls in ballet class. I bet if you looked at how much each of the girls identified themselves as “ballerinas” combined with the emotional conditioning around that belief, you would quickly find that the more successful girl holds very different beliefs about herself as a “ballerina”.

On thing that does come to bear however is the role of brain plasticity at a certain age. If a belief is acquired and emotionally reinforced at a

young age, the brain is more quickly rewired to align with that belief than an adult brain. Any practice performed by the child will also be more effective. To put it in Sean’s terms, the pattern recognition engine in children tends to be more efficient in children than adults. This is also why it often takes a lot of practice for adults to change self-limiting beliefs that were established in childhood.

Sean, it seems that certain skills enable us to acquire other skills more quickly. Call these super-skills or meta-skills. Perhaps an article on what you think those skills are and how to practice them might be worthy of a blog posting.

Brain plasticity in children is stronger in kids because of the factor of ‘survival’ (as far as I know). So in experiments conducted by scientists studying brain plasticity, they found that kids listen, pay attention and learn sounds at first. And that the brain can be trained to accept and work with any sounds–no matter how frustrating or non-useful.

W’hen you turn that around and make the sound or learning useful (as we humans do) then children pick up quickly. The young mind is not able to distinguish between what’s needed for survival and what’s not. This is why a child will willingly head towards a hot object or dangerous object. One of the ways they tend to learn is by the tone (or sound) of their guardian.

In order to survive, and thrive, the brain in a young child is very plastic. But as they grow, the brain starts to form a pattern of what’s needed and what’s not. So the neuron connections are extremely high in young kids. As they grow, those synaptic connections drop, and retain only the ones that are required.

This isn’t to say that adults can’t replicate the system that kids have. The difference between adults and kids is the factor of excuses. When was the last time you saw a two year old come up with a good excuse?

I think that skill is the concept of ‘possibility’ or ‘confidence.’ It’s not a skill at all. People who are good at languages will tell you that they are ‘good at languages.’ As far as I know, any person on the planet is good at languages. I met several “aliens” in Europe. These are folks who left their home in South East Asia. Some of them grew up speaking only one language. But because they had to survive in Europe, they’ve learned Spanish, Polish, German, French and Italian. Some of them knew all of the above languages.

Some of them knew the language of the country they were located in. The point was again, survival. And confidence. They had to blend in, and be able to serve the customer in a kebab store, and so were forced to have to speak. Or starve.

I’m not sure there are skills. I think there are factors like survival, confidence etc. involved.

“The difference between adults and kids is the factor of excuses. When was the last time you saw a two year old come up with a good excuse?”

And behind that excuse is some underlying fear.

Survival is key. As a child we perceive our survival to depend on our parents. Most of us internalize our parent’s tone and internalize their voice to keep us out of danger. However, if we are to continue our progress, there is a point when we must grow beyond this voice of safety and face our fears.

As you rightly state, confidence (or having no other alternative) is the key to facing these fears.

While I do agree that anyone who sets their mind to acquire a skill can, I can”t agree with the “talent is crap” philo.

I have a school friend – he’s an IT manager now – who could within an hour of picking up any musical instrument make it sing. Not the frustrated playing of 13-14 year olds but like a pro who has been doing it for years. No teacher no guidance. Just the instrument. It didn’t matter what type of instrument, string, wind, percussion. At an expert level I don’t know how good he was but to our ears he sounded damn near perfect. Now that’s what I call talent.

Talent, meta-skill, natural affinity (Mike Tyson has a natural affinity to cream his opponent – I very much doubt his achievement was through hard work and practice – more like channeling him in the right direction) or whatever else you might call it is out there – it may not be some magical fairy thing and may have some rational basis – some sort of causative kick that makes it easy for them to excel at that particular thing – excel at it easier than others – like breathing or walking on water 🙂

For the rest of us untalented earth bound misfits the way to the top is to toil toil toil 🙂

This is called ‘pattern recognition’. You have the talent too. When you see a chair, you can (within seconds) tell if the chair is safe to sit on. You can (within seconds) tell if the chair is comfortable to sit on. And yet, you probably don’t consider it to be a talent.

That’s because talent is somehow considered to be for the creative arts. Like singing, playing instruments etc. If your friend lived in a community where everyone could pick up an instrument and play it within an hour, he would be ordinary. No one sits in awe when you and I sit on a chair. Yet we do that when people draw, or sing or do something that we can’t do.

Notice that talent is always linked to something that the general public can’t do. And not linked to something that the general public can do. Why would this be the case? Would you consider getting on a bicycle and riding to be a talent? Yet, in a society that has never seen a bicycle, let alone a bicycle rider, that person would be considered truly talented.

There’s a tendency to mix physical skills with talent. A sumo wrestler will sit on any of us, and crush us. That’s physical strength and nothing to do with talent (unless you consider crushing to be a talent). But when faced with another sumo wrestler of the same size and weight, the physical difference disappears.

Then you have a factor of one sumo wrestler against another. That’s when they have to use their brains to outwit the opponent.

If people were born with talent, they would never need any work to improve the talent. This concept of ‘improving talent’ is fuzzy logic at best.

And it’s best explained with a slightly different take at this post. http://brainaudit.com/blog/?p=152 (Why Kids Can’t Draw)

“talent” or “pattern recognition” amounts to the same thing. Sure its relative to the social context. Sean: your key argument is that talent is not innate but a learned skill (or talent!). There are as many examples for innate affinity to a particular task as there are to learned affinity. But where innate affinity exists it is always more efficient than learned affinity. However, it is just as probable that the one with the learned affinity is more successful (by our definition of success) at deployment.

Ramanujan is another example of innate pattern recognition. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Srinivasa_Ramanujan). If pattern recognition was so easy / or so difficult then we should all be on an equal footing given the same inputs. I doubt any of us would be able to tackle advanced math just by having text books. Likewise I doubt if many of us can pick up a musical instrument and start playing it properly within one hour. For some of us some things are just harder.

Tyson was/is a street fighter. In the boxing ring he needed to stick to the rules. But because of his instinctive pattern recognition of the dynamics of a fight he could zero in on his opponents weakness faster than his opponent and move in for the kill. Maybe he learned to fight (not born a fighter) on the street after getting beaten a few hundred times. And maybe he instinctively imbibed the sequence to triumph over his opponents (as compared to his peers) rather than through rigorous practice at the local gym.

If people were born with talent, they would never need any work to improve the talent

Maybe talent is like a plant. In the early years it grows with you naturally – like walking and talking – later it separates itself out and you need to actively tend to it or maybe your consciousness of it as a separate entity never happens and you happily keep feeding it…or ignoring it…in which case it dies or just remains at a rudimentary level – like a pleasant hobby.

All of us have talent – an innate knowledge about something, which enables us to react faster than others in that particular instance. For some of us it stands out ‘coz the particular talent/skill is not so common in the social context.

Even in a seemingly empty kitchen my wife can whip up a tasty meal. Me? I can only see the Maggi noodles pack. But then again she prefers to not eat out so she has an incentive to discover innovative ways to avoid something which she would rather not do.

Hmmm: I think we should ask the freakonomics guys to dig into this. (http://freakonomics.blogs.nytimes.com). With sufficient data we can settle it properly 🙂

Oh the freakonomics guys have done some work on it already…missed your link …lemme go thro that…

hmmm…the study only included “expert performers” those who excelled in their field … this was a quantitative analysis at best … I wonder how it would show up if you included people like my IT manager friend, the ones who either thro lack of interest or lack of realization that they could excel at their “talent” have not pursued their “gift”

It does answer the question – do you need talent to excel at anything? Answer: NO! It does not answer whether talent is innate or not.

Well it’s impossible when you’re looking at it from your friend’s point of view or Mike Tyson’s point of view. But the innateness of talent doesn’t work, when the person has no access to the information.

That is: A person has had to have access to art to be able to draw exceedingly well. If the talent were simply inborn, you would not need any access. You are born with eyes, ears etc. You don’t need external sources to tell you how to use them. That’s innate.

When you have to learn something and there’s a process, that’s a factor of learning. There are a decent number of books out there: One by Geoff Colvin and another by Malcolm Gladwell. And I’ve been exploring this topic for a while at http://www.brainaudit.com/blog

Hmmm. The way you are defining innateness excludes everything except biological processes. What I am trying to say is that some people have a natural affinity (aka talent) for certain things. That this natural affinity is not observable outside the context of that specific environment (no art without access) does not negate the fact that the affinity exists. Ghengis Khan could have been a piano maestro but for the lack of a piano, and your actual calling maybe as a astro-navigator but for the lack of spaceships. This we will never know (maybe!). However, what is observable is the natural affinity “within the context” – an extra ability that I do not possess when I have access to the same context. Whatever I do I cannot pick up a musical instrument and play it within one hour. Maybe if I devote 10 years (20 years? a lifetime?) to pattern recognizing the principle of playing all musical instruments I can also get there. But my friend had it “in” him. He did not go about acquiring it through any formal or informal process of learning. Ramanujan had it “in” him. A natural affinity for math. Another class of people who have it “in” them are autistic savants.

Conventional thinking (aka society) tries to elevate talent onto a pedestal and everyone gathers around the shining maestro and proclaims “we can’t do that” and everyone else nods in wise agreement and whispers conspiratorially “he has that extra special something” etc which I agree is crap.

However, all of us have something “in” us, a natural affinity for a specific type of task – our talent. And of course it is relative to the normative mean of the abilities present in society. If we could all fly it wouldn’t be a talent – it would be “normal”. Thus many of us have “normal” talents, some of us have “not-so-normal” ones.

Also talent does not equal success. And I am not trying to build a case for needing talent to succeed. But it helps.

Thanks for the authors, will check ’em out. Are you talking about Malcolm’s Outliers? Just bought it, have yet to dive in. Which book by Geoff?

http://www.amazon.com/Talent-Overrated-Separates-World-Class-Performers/dp/1591842247

Let’s put it this way. If you stop believing in talent and instead start believing that there is:

1) No real belief in born talent.

2) A teacher.

3) A process (that speeds up things).

Then you will achieve a lot more in life than if you believe you were born with innate skills. Or to put it another way, you could learn anything you wanted and become exceptionally good at it.

That’s what Outliers explores.

🙂 Let me put it another way:

1. Irrespective whether I have telekinesis I will move that mountain.

2. If I can find a teacher who will teach me telekinesis I will be off like a shot. If I cant find a telekinesis guru I am willing to settle for a CAT D9 guru.

3. I believe there are people who have “innate skills” at moving mountains without the use of clunky clumsy machines.

4. I also believe that you can learn these same skills and “innate” ’em into yr psychic make up so movin mountains becomes a piece of cake and then you begin to wonder about things like moving solar systems and you get a gentle nudge from edges of your consciousness warning you to be careful at that scale.

5. However, since I don’t have a workable theory or a known guru who can help me unleash my telekinetic superpowers I am willing to work the D9 using the most efficient process possible.

6. I will also recognize that all processes have the inbuilt danger of rigidity attached to ’em so I will maintain a flexible “beat the control” attitude, which makes it helluva lot more complicated than plugging 1-2-3-bingo …

…I also recognize that Sean D’souza has some hot stuff bakin in his marketing oven which even though he fails to acknowledge is in fact permeated with some of his own innateness… 🙂

We could go on forever. But to me, talent is a language. It’s teachable, and it’s easy to learn.

Everyone in our lives: Our teachers, parents, and everyone else made sure we believed in talent as something inborn. And we’re entitled to our own opinion.

I can draw.

I have been the lead in musicals.

I know over twenty software programs (some so well that I can be a teacher).

I write 300-500 (or more articles) a year.

I dance exceedingly well.

I have started to take really good photos and will soon be taking outstanding photos.

I know about five languages, and expect to learn at least five more in the coming years.

I can cook well enough to work in a restaurant.

I can coach people, using specific steps and logic.

All of these and more I can do so well that I could be in a university course, or as a coach. And to me it’s hard to believe that I was given all these talents on arrival. In fact, I only have one thing that propels me forward.

And that’s that I don’t believe in talent: Because of that single belief, I don’t need a crutch. And you see that list above. Before I ‘leave the building’ I’ll be adding a few more skills to that. Skills that may not even exist at this point on the planet.

Hmmm. I can’t do any of these things. And its not because I believe I don’t have the talent for it.

Skilling up is largely a mechanical activity. The brute force of intelligence can take you where ever you want to go. Well almost. But, yeah it looks like we are going round in circles over the same bone. Woof woof. 🙂 Natural affinity does exist. Woof Woof 🙂

Aha, now this takes us to a very interesting juncture. So if you believe you can do it, then hey, I can teach you to do it.

And not just teach you, but make you outstanding. And of course, once you become outstanding, you’ll have everyone tell you that you’re um, talented. 🙂

Hi!I think this blog is good!I found it on Google,I will surely come back! 😀